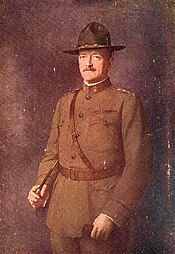

General John J. Blackjack Pershing

On Thursday, Trump gave a shout-out to the late Gen. John J. Pershing on Twitter, reigniting the public's interest in the American military figure. During his service, Pershing got the nickname 'Black Jack,' and while that's an unassailably cool nickname, it wasn't originally intended as a compliment.

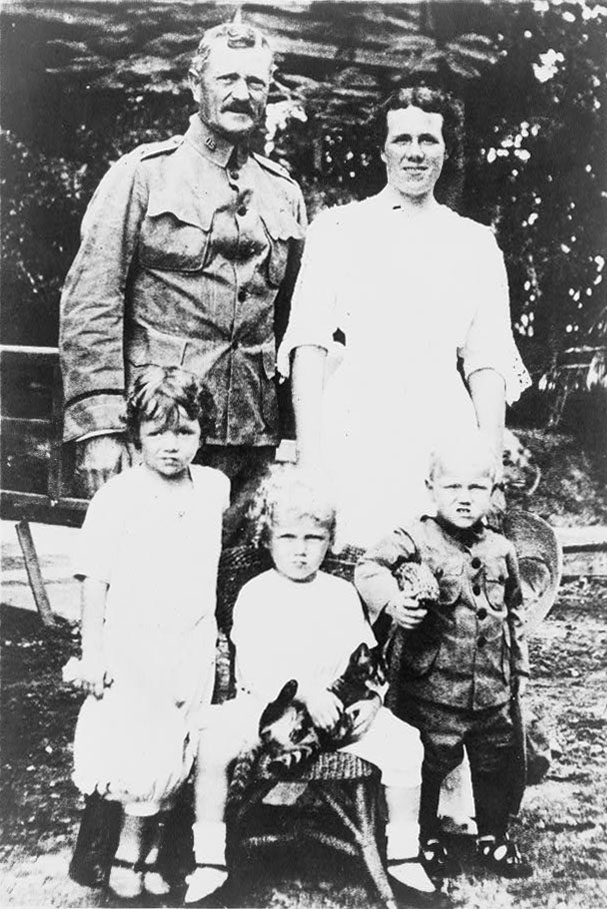

That’s what General John J. “Blackjack” Pershing was sent on by President Woodrow Wilson. On March 15, 1916 the General rode off at the head of about 12,000 troops of the Punitive Expeditionary Force on a mission to find and destroy Pancho Villa and his rebel army in Mexico. Pershing was the only person in history to hold the rank of General of the Armies while serving on active duty. In 1919, to honor his service in World War I, Congress authorized the promotion of Pershing to the rank of 'General of the Armies of the United States' and allowed him to design his own insignia. John Pershing commanded African-American Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry in Montana in 1886 and again in the Spanish-American war in the late 1890’s. The bravery and courage shown by the men of the Tenth Cavalry earned them Pershing’s respect and admiration. 'BLACK JACK' PERSHING - AUTOGRAPHED SIGNED CHECK - HFSID 260346 JOHN J. PERSHING Just two weeks after the Armistice, the soon-to-be General of the Armies pays a newspaper clipping service. Partly Printed Check signed: 'John J. Pershing', 7½x3. Washington, D.C., 1918 November 25.

General John J. Blackjack Pershing Ii

Pershing is most famous nowadays as the subject of a debunked urban legend which claims that he dipped bullets in pig's blood while fighting Muslim enemies in the Philippines. But Pershing had a long career in the U.S. military, commanding U.S. forces in Cuba, the Philippines, and Europe. He's the first and only active-duty officer to become General of the Armies, the highest-ranking position in the U.S. armed forces.

In 1897, Pershing became a tactical officer at West Point, and that's where he was given the nickname 'Black Jack.' There are two different (but not mutually exclusive) stories about how he got that name. According to one tale, Pershing was called 'Black Jack' because he commanded black troops during the American-Indian Wars of the late 19th century. It's also alleged that he was given the nickname due to the harsh, unforgiving manner of discipline he exerted during his time as a West Point instructor.

The first story makes sense. Pershing's first name is 'John,' for which 'Jack' is a nickname, and he was a white man who commanded black troops. Hence 'Black Jack.' The second story is more confusing, though. What does the nickname have to do with being a harsh disciplinarian? The phrase 'black jack' can be used to refer to a card game or a weapon, but nothing about it alludes to an instructor who rules with an iron fist.

Although the answer isn't entirely clear, now is probably a good time to mention that Pershing was initially given a much more reprehensible nickname: 'N-----r Jack.' That one didn't stick, and it quickly gave way to 'Black Jack.' But if Pershing was indeed disliked by his cadets as much as historians believe, and if those cadets did indeed him that nickname in response, that would strongly suggest that Pershing's nickname was intended primarily as a racist insult — an attempt to highlight his perceived negative traits by likening him to a black person and referencing his time commanding black troops.

In any event, Trump was harshly criticized by Democrats and Republicans alike for giving new life to the discredited pig's blood myth, endorsing religious bigotry in the U.S. military, and mischaracterizing the service of a celebrated American general. Right-wing blogger Jennifer Rubin wrote on Twitter that, in light of Trump's Pershing comment, she's giving new consideration to the argument that Congress should remove Trump from office by invoking the 25th Amendment.

The installation of the Venustiano Carranza regime in Mexico City did not result in lasting tranquility with the United States. Events became so chaotic that the State Department issued a warning to U.S. citizens living in Mexico to leave the country. Thousands took the advice. One of Carranza’s allies, Francisco “Pancho” Villa, turned against the new president, claiming with some justification that Carranza was not making good on his reform pledges. Villa himself was a rascal, an enormous self-promoter and an occasional champion of the underprivileged. Villa was initially engaged in a struggle on behalf of the government against rival forces. He became the darling of Hollywood filmmakers and U.S. newspapermen by granting open access to his campaigns. Some claimed that he actually staged battles for the cameras and publicity.

Villa's horizons broadened considerably when he began to seek control of the Mexican government for himself. His method was to weaken Carranza by provoking problems with the United States. On January 10, 1916, his forces attacked a group of American mining engineers at Santa Ysabel, killing 18. The Americans had been invited into the area by Carranza for the purpose of reviving a number of abandoned mines.

Pancho Villa’s men struck next on March 9, by crossing the border to attack Columbus, New Mexico, the home of a small garrison. The town was burned and 17 Americans were killed in the raid. War fever broke out across the United States. Senator Henry F. Ashurst of Arizona suggested that “more grape shot and less grape juice” was needed, a none-too-subtle indictment of the teetotaling secretary of state William Jennings Bryan.

President Wilson abandoned 'watchful waiting' and appointed General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing to head a punitive force of 12,000 soldiers to locate Villa — dead or alive. Carranza was not enthusiastic about the incursion of an American army onto Mexican soil, and became even less so the farther south the soldiers marched. Despite several close calls, Villa always managed to escape the larger and better-equipped invaders. An exasperated Pershing cabled Washington: “Villa is everywhere, but Villa is nowhere.”

The chase lasted nine months and finally ended in February 1917, when Wilson summoned the soldiers home in anticipation of imminent hostilities with Germany.

A new Mexican constitution had been adopted in January 1917. The document sharply reduced the powers of The Roman Catholic Church and foreigners, which reflected popular disgust with those two elements of oppression. Carranza was formally elected president by a democratic vote and was recognized by the United States. Pancho Villa was a popular hero in many quarters in Mexico, but had also made many enemies over the years. He was ambushed and killed several years later, probably at the instigation of then president Obregon.